Swearing in writing. This is something of a taboo. None of the children’s books you read growing up will have contained any swear words; it is un-Christian (and blasphemy in any religion is

discouraged), it is socially unacceptable, it is age-inappropriate, it would plant words into the vocabulary of children which are unacceptable in school environments. As you grew older the books or magazines you chose to read would have been edited with the age of the audience in mind or they wouldn’t have been allowed on the shelf. Books selected by schools for the curriculum would have had your level of learning and appropriateness of age as well.

Swearing in speech. Now this is something which, with each passing generation, the social standards seem to be slipping on. Language fit only for the dock yard or a building site is now part and parcel of everyday speech for some people and it is not uncommon to hear it frequently in the presence of children. While I have read arguments that the use of swear words demonstrates a lack of intelligence, a poor command of vocabulary and further evidence of a degenerative society I would like to argue that is has become part of our cultural heritage. Indeed, swearing often adds impact to what we are trying to say and I believe in some parts of the country an emphatic statement can only be made in certain social environments by including such colourful language. Given the full power of the entire English dictionary, one would not make their message – and the strength of one’s sentiments – entirely clear if speaking the Queen’s English. Furthermore, if communication is only effective when a message can be transferred successfully, efficiently and cohesively from one person to another then surely it is of the utmost importance to use language that the receiver can understand and therefore decipher. Language is after all, in its simplest form, a set of codes to be communicated and understood.

‘Nobody move! That lassie got glassed and no c**t leaves here ‘til we find out who what c**t did it.’ – ‘Franco’ Begbie, Trainspotting (1996).

There are a few things to note regarding the statement above. Firstly, I have quoted it as I heard it in the film – the link is at the bottom of the blog for those interested – as Welsh’s Trainspotting is often written in the accent being put across (more information on this can be found in last week’s blog). Secondly, the line is delivered with aggression as Begbie is actually spoiling for a fight having thrown the glass which injured the girl himself; that said, it is also delivered in a humour of sorts as he is looking forward to the fight that follows knowing full well he is the perpetrator of the offending act. Thirdly, while the sentence may appear disjointed and grammatically incorrect to us it is anything but to anyone from within that social environment who has shared his cultural background. Swearing can therefore not only be socially acceptable but in some cases it may be imperative to use swearing in order to be accepted socially. Finally, while films have to be rated for the appropriate audience prior to being made public this blog is under no such obligation. It is therefore my own editorial choice to have censored the swear words for the benefit of the readers – in this instance, yourselves – as well as the publisher. If we were to have referred to blasphemy of Shakespeare’s time by quoting ‘S’blood’, which is of course short for ‘God’s blood’, I doubt I would have censored it at all whereas this particular swear word still offends large groups of people and I have no wish to unnecessarily offend anyone.

This brings us to the writing element of the use of swearing and that is the editorial process. David Lodge quotes Mikhail Bakhtin as stating that ‘For the prose artist the world is full of other people’s words, among which he must orient himself and whose speech characteristics he must be able to perceive with a very keen ear. He must introduce them into the plane of his own discourse, but in such a way that this plane is not destroyed.’ (1992, 128). So when considering your novel or short story ask yourself: does the inclusion of cursing add to the dialogue or detract from the quality of it? Perhaps there are other ways to illustrate a character’s frustration which would reduce the use of swearing as the sole vehicle of frustration and anger. It could be that perhaps a fists slams against a door, tearing at one’s own hair, kicking an object or – if swearing was used to highlight despair – the character may slump to the ground. These are of course choices for you to make and there are many others besides the few proposed here. Ultimately, what I want you to think about is that if swearing is employed to make a particular character seem angrier or a situation appear more tense then when is the best time to use it for dramatic effect. Once you have decided, use it sparingly to make your writing of these passages better and not to dilute the quality of your work.

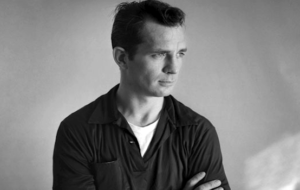

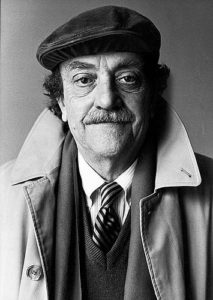

The other scenario when swearing is used is in speech and we have already discussed a few factors which contribute towards this. John Mullan states that ‘Swearing tells us of the real world of emotions out there.’ (2006, 153) and while this is true it does not account for people who censor themselves; it is undeniable however that in some circles swearing is an everyday occurrence in language. This is one of Trainspotting’s charming factors. The novel is heavily laden with cursing and yet the characters would not be authentic without it. I made reference in last week’s blog that fiction smooths speech so maybe Irvine Welsh included more swearing than was natural for that social environment, maybe he made Begbie’s line of enquiry above more comical and maybe, just maybe, he removed language which would not have ‘travelled well’ in order for the novel to reach a wider audience. Whatever he did, the series of novels following these characters are hugely successful and it would be worth reading at least one in order to identify some of the techniques used and choices made.

Rather than invite a plethora of profanities onto Candy Jar’s website I would prefer you instead to think creatively about this topic. Therefore, if you have already produced some writing which contains a lot of swearing it may be beneficial to revisit an extract of it and revise your work to try and replace some of the phrases containing swear words with descriptive phrases which tell us of the character’s frustration or anger instead. If you haven’t yet written anything containing curses it might be an idea to document some phrases which are particular to your or your kin when you are frustrated or angry (no need to share this just yet).

Finally, if you wish to see a topic discussed which you haven’t seen yet then please let me know and I’ll include it at some point. Happy writing!

A blog by Steve Marshall

—

Further reading:

Lodge, D. (1992) The Art of Fiction. London: Penguin Books.

Mullan, J. (2006) How Novels Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Welsh, I. (1993) Trainspotting. Secker and Warburg: London.

Video link:

In last week’s blog I asked everyone to have the courage to write. To write something, anything. Writing may come easier to some than to others so it got me thinking about where writing begins.

In last week’s blog I asked everyone to have the courage to write. To write something, anything. Writing may come easier to some than to others so it got me thinking about where writing begins.